Moving target: the low down on booking curves in a post-recession world

As we move out of recession, revenue managers must be more proactive about anticipating when bookings will come in, writes Tom Bacon

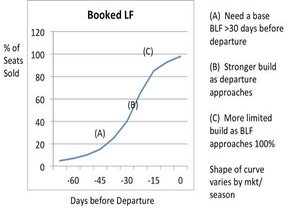

Booking curves have historically been the basis for airline revenue management, but this could be on shaky foundations. Booking curves plot bookings against days-before-departure and show how a flight fills up over time. Normally, bookings begin at a slow pace, begin to accelerate as you get closer to departure, and level off as the flight nears 100% load factor:

Using statically derived averages, the RM system predicts how many bookings will come in before the flight. For example, if a flight is booked 42% 21 days out for a specific flight, based on statistically derived booking patterns, the system might forecast that the plane will be full and that you should limit availability of the lower fares. Of course, RM systems analyse booking patterns for different types of flights – and different seasons - in predicting ultimate demand and allocating scarce seats. Flights during peak holiday periods tend to book further in advance; flights in business markets tend to book closer to departure. In each case, the RM system uses the historic booking pattern to forecast ultimate demand for the flight and ensure there are enough seats set aside for any forecasted close-in high-fare demand.

I was in charge of revenue management for a $1bn carrier during the 2008 recession. During that period, the historical booking patterns didn’t work for us:

· With relatively poor bookings 21 days out, the system expected the flights to have empty seats. However, the uncertainty everyone felt during the recession served to delay, not eliminate, most bookings – demand showed up in the last 21 days and flights were quite full.

We were forecasting bookings based on a shaky foundation – the booking curve had changed its shape. Can the RM System – or you –accurately forecast such Changes in the booking curve?

In 2008-9, at the beginning of the recession, the booking curve shifted to be closer in. Arguably, this was a temporary phenomenon at a particular point in an economic cycle. However, for a number of reasons, the booking curve has stayed closer in – and I expect it will continue this shift going forward. Even though the economy has largely recovered from ‘The Recession’, there are many factors that continue to drive closer-in booking activity. In my view there are three reasons for this:

1. Customer Demand for Flexibility

Customers want flexibility in travel planning. They all love the idea that they can use their mobile devices to pick flights spontaneously or book a room while on the road. Leisure travellers want to take a trip this weekend; business travellers work in ‘real time’. ‘Instant gratification’ is moving to travel planning. And, new airline fees support this behaviour as travellers wait to book their flights rather than subject themselves to high change fees (many US airlines charge $200 for domestic changes).

2. Ancillary Fees

Customers used to book out long before 21 days out to get the best fares. But now those low fares are subject to higher fees – bag fees, change fees and so on. Some airlines are getting 40% of total revenue through fees – and, in many cases, the percentage is highest for travellers booking far in advance. With new ancillary fees, customers have less incentive to book that far in advance.

But it’s not just a demand-based story….

3. Higher Loads

Third, as airlines have adjusted capacity across the US, average load factors have increased. Given the new balance of supply and demand, airlines tend to truncate the normal booking curve, not selling as many lower fare seats further out. Airlines are working hard to keep seats available for higher fare/closer in bookings. Instead of a 40% booked load factor ‘goal’ 21 days out, airlines are pleased with a 30% booked load factor, leaving 70 percentage points for closer-in (higher fare) demand.

It’s not over yet

The change in the booking curve isn’t over. As mobile grows, as airlines continue to adjust capacity to demand, and as ancillary fees reduce customers’ incentive to book further out, bookings will occur later, further compressing demand. The booking curve will continue to shift toward the day of departure with more and more bookings occurring within two or three weeks of departure.

Revenue managers need to be aware of this trend, even while unable to predict exactly when and how much further ‘compression’ will occur. Revenue managers need to constantly test the validity of historic booking curves – testing whether or how much demand may have moved closer in. Rather than wait for your RM model to alert you to a change in the booking curve, RM managers must anticipate changes and adjust the model accordingly.

This story is by Tom Bacon, 25-year airline veteran and industry consultant in revenue optimization.

Questions? Contact Tom at tom.bacon@yahoo.com or visit his website http://makeairlineprofitssoar.wordpress.com/