Internet marketplaces: Is it time to level the playing field?

Marketplace websites like Airbnb and Gidsy are hugely popular but in many cases using them can conflict with local laws and regulations. Andrew Hennigan investigates growing questions around the use of these sites and wonders if authorities will continue to turn a blind eye

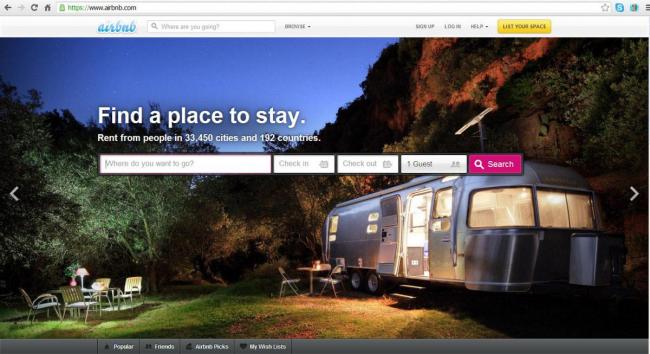

When e-Learning expert Julie Attard travels from her home in Grenoble, France, she often chooses to stay in homes she rents through Airbnb, an Internet marketplace for accommodation (see Airbnb on the importance of creativity, quality and having commitment, EFT, 13 December 2012 ).

“I use Airbnb because it’s a great alternative for travellers on a budget,” she explains, “and also because I travel a lot and I am tired of hotels and restaurants.” Attard also rents out her own home through Airbnb. “I like meeting new people and when you love the place you live in and have the opportunity to make other people discover that too, it’s great!” Dave Elchoness, the chief executive and founder of Internet startup Tagwhat in the USA, also finds the service useful and not just for leisure trips. “I’ve used it when on business because it is a cheaper alternative,” he says.

Many others echo these sentiments, but there are some questions about the legality of these rentals, which may in certain cases contravene local regulations. Many cities have rules that require owners to have some sort of license before they rent their properties; others have reporting requirements and in many instances there are tax issues. In addition, there are concerns around liability. If something goes wrong in a hotel there is liability insurance, but people renting private properties are not protected in the same way.

Consumers are mostly aware of this discussion, but few are discouraged. “I haven't had any concerns about liability,” says Elchoness, an attorney himself. “I haven’t really thought about it. I sleep over and leave. Complaints must be coming from landlord associations and hotel associations who want to maintain the status quo.”

A growing concern

Others are more worried about the potential for abuse where businesses use Airbnb. “It should only be for those who live in the homes being rented,” says Attard. “For landlords to make money this way is not acceptable”.

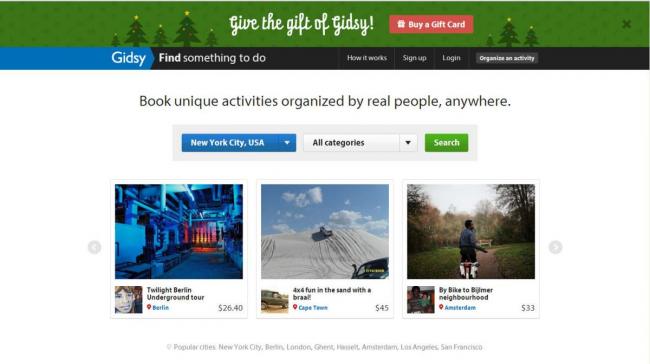

Other Internet marketplaces face similar issues as they explore previously uncharted regions of the business landscape. Gidsy, the marketplace for experiences (see The rise of Internet marketplaces: threat or opportunity? Eye For Travel, 28 August 2012), allows anyone to organise an activity for other people anywhere in the world. Users of this service can also fall foul of local regulations. For example, the owner of a light airplane could make some money and meet new people by organising aerial tours through Gidsy. However, in many countries this would require a commercial pilot’s license. Other activities are also regulated in some way – especially anything involving food or dangerous sports.

Nothing new

While such issues are attracting more attention today they are hardly new.Steve Brenner, an American based in Rome, owns the Beehive Hotel in Rome. Since 2000, he has also had his own web-based rental service Cross Pollinate and for good measure he has used Airbnb himself. Unsurprisingly he has a broader perspective on the issue.

“In Italy there is no law or restriction that prevents someone renting their property on Airbnb or any other site,” he says. However, he is quick to add that there are many laws that have to be respected to get authorisation to rent a property legally. “Then there are laws that should be respected involving registering guests and collecting a tourist tax,” he explains.

Very often these rules are not applied strictly, if at all, but it does happen. “There aren’t any prosecutions because it isn’t a penal crime,” explains Brenner, “but in major cities there are checks by the local police and they give fines”.

As Brenner points out most sites either want to see documentation of a license to rent a property before they listing it. At the very least the property must have in their terms and conditions that the property is legal. “I think that's quite easy, if the intent is to only have legal places,” he says, adding that: “It's clear that in an AirBnb model, that doesn't work because they really aren't looking for those kinds of renters.”

Being both an hotelier and an Airbnb user Brenner can see both sides. “Competition is fair if it’s on a level playing field,” he says, “but a hotel that is competing with an unauthorised room for rent is a not very level playing field.” On the other hand he has listed on Airbnb himself – including his own apartment. “Airbnb was clearly designed for apartments and single rooms,” he adds, “and it doesn’t work so well for people with multiple rooms such as hotels”.

Marie-Reine Jezequel is another pioneer who founded an online rental website, NY Habitat, in 1989, long before marketplaces emerged. She recognises the need for new rules.

“The vacation rental industry is in dire need of regulations,” she says, “and the introduction of New York’s Short Term Rental Ban in 2011 did not solve the problems the industry is facing.” NY Habitat chose to respect the new restrictions and purged their inventory. “But paradoxically online peer-to-peer rental websites [like Airbnb] have multiplied and prospered,” she says. This is because individuals using the sites have chosen to ignore the regulations, while authorities seem to be turning a blind eye. “Legislators should provide clear incentives to online rental marketplaces to self-regulate and develop mechanisms to monitor compliance and confirm the legal and tax status of the properties they advertise,” she stresses.

Airbnb is well aware of these discussions and says it supports the drive to bring more clarity to regulations. “We agree with the spirit of regulations that seek to protect hosts and guests alike,” says Christopher Lukesic, a spokesperson for the company. “We would support any legislation that would make it easier for permanent residents to rent out their extra space occasionally,” he adds, “and for travellers to access local neighborhoods and bring additional income to the city.”

However, as Brenner points out the laws vary so much from place to place that it would be tough for a company like Airbnb to try and lobby to allow their kind of rental. Airbnb has offices in Italy and France and elsewhere. “It's not like they don't know what can and can't be done and couldn't put it in a ‘legal’ section of their backend,” he says.

Not easy

Making this happen within the existing legal framework will not be easy and the speed at which laws change will vary depending on where you are. “In some places where entrepreneurship is valued and encouraged I can imagine the laws bending towards the marketplace,” says Brenner. “New York might go this way. Italy won’t and I doubt Paris will either.”

But others, especially in the startup community, view these changes not only as inevitable but also critical for the future of the economy. “Since this model of peer-to-peer marketplaces is so new there are definitely things that need to be figured out and some questions that need to be answered,” says Gidsy chief executive and founder Edial Dekker. But at the same time he believes that the new models can be inherently more robust. “Platforms like Airbnb and Gidsy are more decentralised, which creates some friction sometimes, but I believe in an economy that is more deregulated than today, an economy that is more agile and less fragile.”

We’ll be watching this playing field with interest.