Hotels and the dirty battle of distribution

From point-of-sale shenanigans to wholesaler tactics and the rise of club rates, hotels of all shapes and sizes are fighting back and it’s not over yet, writes Pamela Whitby

The battle for direct bookings in the hotel space is hardly new. However, an interesting recent turn has been the decision of a number of big chains to introduce highly preferential club rates to loyal members. Bouyed up by its recent marriage with Starwood, Marriott may have been the first to move but Hilton, Hyatt and IHG did not waste any time following.

Others are watching closely to see whether the OTAs will use ‘ranking’, one of their most powerful weapons, to push participating hotels down the list. In the short-term, some believe this is likely, but if more hotels have the guts to join the march – all 186,000 of them globally, according to STR Global - then the OTAs may need to do a bit of head-scratching.

After all, the OTAs are in the business of making money, and ranking their biggest partners down, or playing hardball on the issue of club rates, could ultimately backfire on their bottom line. It could also be seen as a declaration of war. More likely, they will find other ways to generate new revenues.

David & Goliath

So it’s clear that today the big chains have more leverage with the OTAs. But some smaller and medium sized chains are also proving to be feisty outliers in the direct bookings’ battle – relatively new hotel tech upstart CitizenM is one and budget brand Premier Inn is said to be another.

Aside from the shifts in rate parity rules in Europe, which paved the way for closed user groups and the ability to offer club rates, sophisticated tools and data-driven technologies are making this possible.

Says Lennert de Jong, chief commercial officer, CitizenM: “Modern technology is allowing more and more hotels to be aware that they are being undercut in a number of channels”.

Having said that the battle is anything but over and hotels – and small and medium sized chains, in particular – still face numerous distribution challenges.

One of the issues is this: the three channels that hotels rely on most for direct bookings – Google, Metasearch and Display – also happily take a large chunk of revenues from the big OTA boys. Google’s biggest clients are our two favourite OTAs, around 50% of metasearch revenues are generated by OTAs and in the display space firms like Criteo, although they won’t say what the split is, also count OTAs as big customers.

In a similar vein, is the issue is point-of-sale pricing which de Jong sums up neatly with this personal experience.

“I have a friend in Argentina who cannot understand why the price of a hotel in Amsterdam searched for in Buenos Aires can be much less than the rate seen by his parents living in Holland,” he says.

What is happening here is that OTAs are using their sophisticated technological prowess to aggressively apply point-of-sale pricing in highly competitive and varied regional markets. So while the hotel might be able to control parity on the home front, often a country that is their feeder market is undercutting their Best Available Rate.

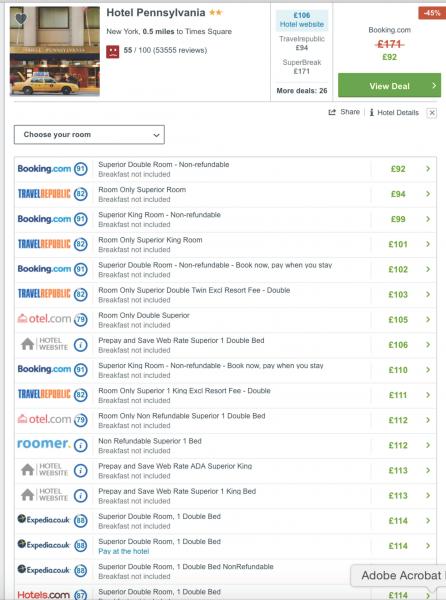

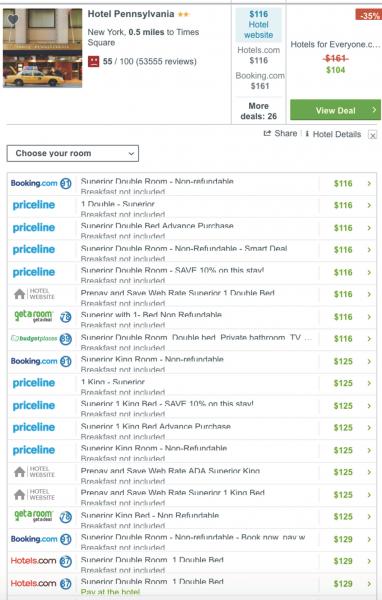

To highlight the point, take a look at the hotels.com rate towards the bottom of the two images below which were searched for on the same day in the UK and US respectively.

Here below on the the UK site, the rate for a superior double room is £114.

Whereas here, on the US site it’s $129, which converts to around £89 – a difference of £25.

According to Dori Stein, CEO, Fornova, a technology firm helping hotels address this problem, there are thousands of examples like this: “When we work with hotels, in a matter of every few weeks there is a new OTA that they have never heard of with rates that they are not supposed to have, that are totally undercutting the hotels.”

The problem of super low prices showing up on random OTAs is the result of wholesalers selling off inventory, with unrestricted rates

Dori Stein, CEO, Fornova

It’s not that OTAs are being intentionally sneaky here. “The problem of super low prices showing up on random OTAs is the result of wholesalers selling off inventory, with unrestricted rates,” Stein explains. (More on this practice here: Hotels, the wholesaler hell and the fight back EyeforTravel June 25, 2015).

Not good, especially when you consider that research shows that in most countries consumers choose to book direct if the process is simple and the rates are comparable. However, the consumer cares most about price, they will double-check, and if it’s cheaper with a third party that’s where they will spend their dosh. This is a quadruple whammy because the hotel has lost:

i. Brand integrity for having its best-available-rate beaten by a third-party

ii. Direct booking revenue

iii. Commission to the third-party OTA

iv. Pay-per-click revenue to the meta

Clearly this is a growing problem, and one that the world’s biggest OTA is already looking to capitalise on. A booking.com spokesperson had this to say:

“From the ongoing dialogue that we have with our partners on a local level, we understand that providing them with the ability to compare how their rates are being displayed across multiple distribution channels would definitely be of interest. As such, we are currently developing tooling to meet this demand for interested partners and will be able to share further details on availability and specific functionality over the coming months.”

Staying in control

Such point-of-sale shenanigans are exactly the reason why Dutch chain CitizenM shies away from the merchant model, where they do not control the end price.

“Whenever the customer starts paying someone else and you get the net result of it you never know what the customer has paid that other party,” de Jong says.

While staying away from any party that doesn’t control the end rate might be CitizenM’s end goal, that isn’t always straightforward.

OTAs also want to give their hotel consumers choice – hence Expedia offering both Hotel Collect and Expedia Collect. So another big question arises: will Expedia allow hotels to dictate whether they do one or the other? Probably not.

Another challenge hotels face is that of affiliates passing on discounts to consumers. Of course, it is a known mechanism that OTAs redistribute the hotel's rates and inventory to other websites; sometimes to car rental sites or airlines websites, but more often to affiliate websites which take a cut for every reservation they book.

But that often doesn’t work in the hotels’ favour.

Says De Jong: “We had people staying repeatedly in our hotels who did not want to book direct. When we asked why, we learned that they receive cash for their stay using Quidco, an affiliate website of multiple OTA's.

Why would we give a double-digit commission to an OTA only to find out that half is given back to the consumer in cash by an affiliate of that OTA?”

Why would we give a double-digit commission to an OTA only to find out that half is given back to the consumer in cash by an affiliate of that OTA?

Lennert de Jong, chief commercial officer, CitizenM

Watertight contracts

Clearly, staying in control of the direct channel is what all hotels dream of. However, CitizenM arguably has the advantage of being a relatively new chain without the complication of legacy systems, a clear brand agenda, and a small number of hotels in big cities where occupancy rates tend to be higher.

On the other hand, resort hotels and chains that rely on more seasonable business still depend on wholesale contracts, and also on healthy partnerships with the OTAs.

“The wholesale business has always been around and is still necessary in some cases, but many hotels haven’t put enough effort into ensuring that their contracts reflect what is happening in the rest of the distribution chain,” says Asa Murphy, a former executive at Nordic Choice and now owner and CEO at BizStrat.

This has to be a priority. Marco Corsi, who manages third-party distribution at Finland’s biggest chain Sokos Hotels argues that if they haven’t already hotels really need to get to grips with their rating strategy and the finer points of their contractual obligations.

Generally speaking rates fall into three categories:

i. Direct- the one’s hotels publish and have full control over

ii. Semi-controlled– those where they have parity with OTAs

iii. Uncontrolled - such as static wholesale rates that haven’t been contractually secured

Uncontrolled rates are, needless to say, the biggest headache and need to be addressed urgently but Corsi believes that there is also room for negotiation and greater flexibility, especially with respect to inventory parity, in other agreements. This could also work in the OTAs favour.

For example, right now Corsi is unwilling to direct marketing spend towards a point-of-sale promotion with any OTA. Why? Because that discount must then be offered to all OTA partners. “It’s not a promotion, it’s a general rate discount,” he explains.

However, if Corsi could offer a discounted rate as part of a limited and targeted point-of-sale promotion with just one OTA, but in a market where Sokos didn’t have visibility, then he would be willing to risk a non-profitable campaign for longer term gain.

The more hotels realise this and demand it, the more OTAs will be driven into a corner with rate parity demands.

So the OTA-Hotel battle is not over and the rules of the game are changing.

Interestingly de Jong has this to say: “Today booking.com is the only OTA which is playing – and has to play - the game fair and square because it only sells commissionable agent rates.”

‘Fair and square’ is not usually a phrase one would associate with the world’s biggest OTA but as we see time and again in this cutthroat world of hotel distribution, perhaps there is a first time for everything.

Upcoming hotel content includes a handy outline of Distribution Dos and Don’ts for hotels, a free video revealing more insights from CitizenM and an interview with Starwood’s head of digital. Or join us at one of our upcoming events for networking opportunities and insider views